Material contribution to damage applies to indivisible injuries, but how?

Holmes v. Poeton Holdings Ltd [2023] EWCA Civ 1377.

The forensic debate as to the correct application of a concept of material contribution to damage has run in the Courts for almost as long as The Mousetrap has run on the West End stage. In Holmes v. Poeton Holdings Ltd, the Court of Appeal has attempted to reach a definitive conclusion to this debate. However, in the judgment of Lord Justice Stuart-Smith disapproval is expressed of obiter statements in both the Supreme Court and the Privy Council. It therefore remains to be seen whether in respect of the forensic debate, this will be the last night of the show.

The essential facts of the case can be briefly stated. The Claimant, whilst employed by the Defendants, was exposed to a harmful substance, Trichloroethylene (“TCE”), in breach of duty. The Claimant subsequently contracted Parkinson’s disease, which is agreed to be an indivisible condition in the context of the claim. At trial, the Claimant accepted that the scientific evidence was insufficient to prove that the Claimant would not have contracted Parkinson’s disease in the absence of TCE exposure, that is “but for “causation. The Claimant contended he was entitled to succeed on the basis of material contribution to damage. The Judge found for the Claimant on causation .

The first ground of appeal was that the Judge was wrong to hold that the Claimant could succeed on material contribution to damage in the context of an indivisible injury without proving ‘but for’ causation. The Court of Appeal rejected this argument. In a detailed review of the authorities, Lord Justice Stuart-Smith acknowledged that there were conflicting judicial statements and academic criticism of the reasoning in Bailey v. The MoD. Nonetheless, he concluded that the decision of the Court of Appeal in Bailey v. The MoD was correct on its facts. Lord Justice Stuart-Smith, with whom the two other Judges agreed, therefore did not accept that the only exception to ‘but for’ causation in tort was the Fairchild exception, which it was accepted did not apply on the facts of the case. Similarly, Lord Justice Stuart-Smith did not accept, as had been apparently stated in Williams v. Bermuda in the Privy Council, that material contribution to damage was merely a context-specific way of applying ‘but for’ causation. Whilst the reasoning of the Privy Council had been brief it was generally understood as indicating that material contribution applied where although the Defendant’s agency was one of a number of causes it was a sufficient factor as to be considered a but for cause.

The Defendants’ Appeal, however, was successful. Lord Justice Stuart-Smith held that the Judge had been wrong to consider that generic causation of Parkinson’s disease by TCE was established on the scientific evidence before the Court. He further indicated that the Claimant could not succeed in relation to individual causation because the Judge’s findings had not identified any specific factors which would have led to proof of causation in the absence of a finding of generic causation. This was particularly the case because the Judge had only made vague and general findings as to the extent of TCE exposure. This part of the judgment, and indeed the Defendants’ apparent concession that TCE was a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, appear incongruous. If proof of generic causation failed, then the Court was indicating that there was no satisfactory evidence that TCE could cause Parkinson’s disease. In these circumstances, individual causation would not arise nor would TCE be a risk factor. However, in the circumstances, a failure to prove generic causation was in itself sufficient to result in the claim being dismissed.

If “material contribution to damage” is established as an exception to ‘but for’ causation, then given its exceptional nature, the scope and application of the concept need to be clearly defined. The experience of practitioners is that this has not been the case, in particular since the decision in Bailey v. The MoD. Rather, the concept is relied upon as what might be described as a forensic ‘Get out of jail free’ card in cases where the Claimant has the beginnings of a case on causation, but realistically acknowledges that ‘but for’ causation cannot be proved. This lax analytical approach is well evidenced in the findings of the Judge at first instance. The Judge discussed a number of aspects of the evidence, including the Claimant’s excessive exposure to TCE and the scientific evidence which indicated at least the possibility of risk from such exposures. He concluded at paragraph 83 of the judgment:

“… If I stand back and ask myself whether the propositions set out above persuade me that in this particular case, on the balance of probabilities, was the Claimant’s Parkinson’s disease materially contributed to in fact by his exposure to TCE at the Defendant’s works, then the answer is yes. In my view, to conclude otherwise would be to suspend the reality of the situation and ignore that which on any analysis seems to me to be the likely reality. Ultimately this decision is a matter for the Court, guided of course by the expert evidence. It is not a matter of formal epidemiological analysis.”

It is impossible from this passage and the judgment generally to consider what the Judge actually understood by the concept of material contribution in fact.

Given the Court of Appeal’s finding that the evidence did not support generic causation, there was no further basis for discussing whether there was sufficient evidence to consider how material contribution to damage might be evaluated. On the Court of Appeal’s finding, the Claimant did not get to first base.

In referring to material contribution in fact, the Judge was at least recognising that material contribution to damage as a legal concept requires proof that the Defendant’s agency contributed in factual terms to the causation of the injury, as opposed to creating a risk of the injury occurring. In the latter situation, absent the application of the Fairchild exception, then the approach in Wilsher would result in the claim failing. In CNZ v. Royal Bath Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, on a secondary ruling as to causation, Mr Justice Ritchie considered that a Claimant was entitled to 100% damages in terms of functional outcome, even though the Claimant would have been brain damaged in any event on the premises of the secondary ruling. However, critical to this approach was his finding that a negligent delay in delivery had caused most of the Claimant’s brain injury on a ‘but for’ test. His approach therefore was consistent with the subsequent decision of the Court of Appeal in Holmes but was premised on a “ but for “ finding of actual causation of significant damage.

It is then necessary to consider what is meant by “material” in this context. Here the Courts have maintained a stubborn insistence on reflecting a historic test that “material” means not de minimis. “De minimis” is an arcane and impressionistic concept used by the courts in the 16th century to determine a dispute about tin mining. It is not appropriate where there is detailed and sophisticated scientific evidence capable of establishing what material effect a breach of duty could have. The difficulties created by continuing to use the de minimis threshold were put into sharp focus by the Court of Appeal in the case of Carder v. The Ministry of Defence. The Court reached a conclusion that a contribution to an injury by a Defendant at a very slight level was insufficient to cause any difference in functioning, but nonetheless was not de minimis. This analysis was inconsistent with the approach to material injury establish by the Supreme Court in Rothwell & Others, that is being appreciably worse off in terms of functioning. It is reasonable to accept that material in this context should have the same meaning as in other legal concepts such as material misrepresentation or material non-disclosure and indeed material injury that is at least capable of making a difference to the outcome.

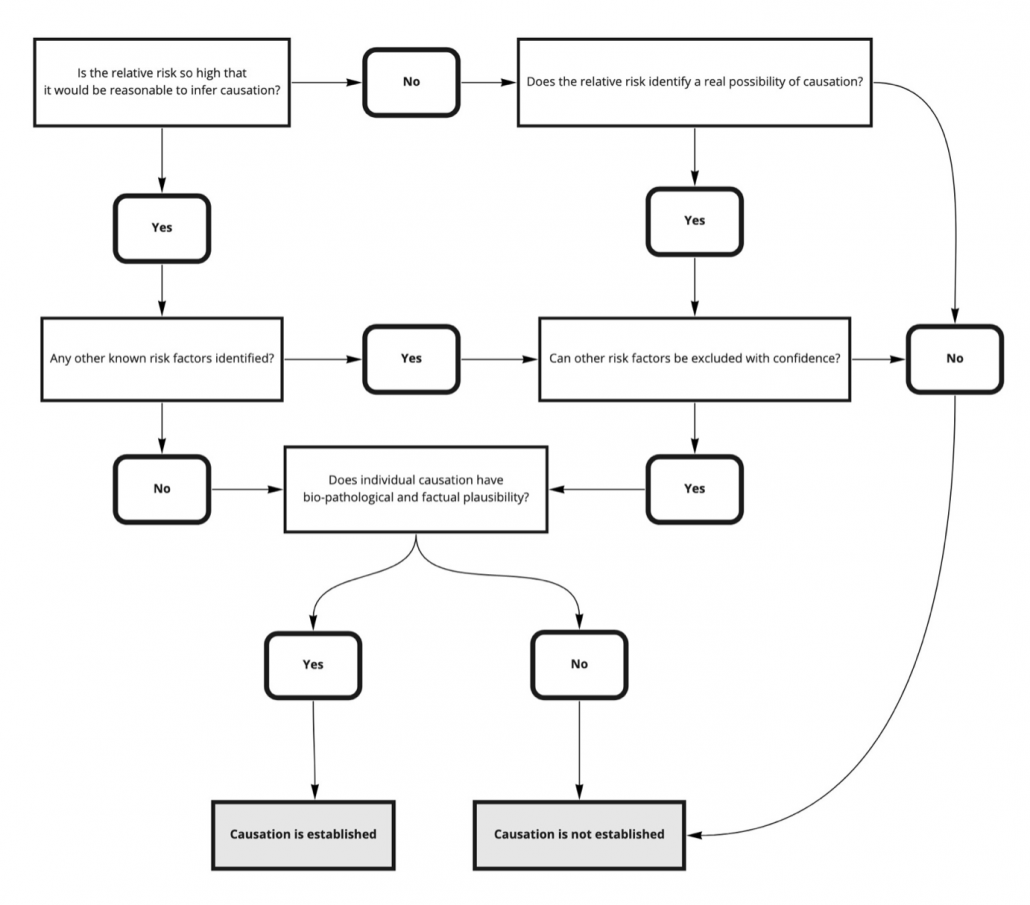

Considering the likely outcome if a finding of generic causation was reasonably made and no other risk factors was identified, then it could be argued that the Claimant would have succeeded without having to resort to any exception to ‘but for’ causation. In these circumstances, the Claimant would have demonstrated a significant increase of developing the condition from the Defendant’s breach of duty, with no other likely causal factor being implicated. Per Laleng and I discussed this situation in a paper published in the University of Western Australia Law Review, “Law in epidemiological evidence: Double, Toil and Trouble”. The suggested approach to causation was set out in an algorithm:

Although there are suggestions in the judgment of first instance and the Court of Appeal decision in Holmes that doubling of risk may be critical in this context, we argued in the article that material increase would be sufficient in the absence of any identifiable other causal factor.

If, on the other hand, other potential causal agencies were identified then it would have to be considered whether these could have operated cumulatively so as to cause the disease, or whether the different potential agencies were independently of each other likely to cause the disease. In the latter situation, again, the circumstances would fall within Wilsher and the Claimant could not rely on the Fairchild exception.

If, however, the causal agencies were cumulative in effect, then the application of a concept of material contribution to damage would result in the Claimant succeeding, even though the Claimant could not overcome the ‘but for’ threshold on basis of the decision in Holmes. It would of course be possible for the Defendant to argue that the injury would have occurred in any event, but if a reasonable approach is taken to the assessment of materiality, it is difficult to envisage a case where the Defendant would succeed in these circumstances.

Therefore, material contribution to damage is probably going to continue to run, as with The Mousetrap. There will be hopefully a difference in the plot with the focus being on the meaning and assessment of materiality.

Charles Feeny